- acacia.marshall's Blog

- Log in to post comments

Valentina Farinelli and Jon Hopkins

In June 2020, following the first Covid-19 lockdown, the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery produced the report 'Towards a robust, resilient wellbeing economy for Scotland' (or the 'Higgins report') which provided the Scottish Government with advice on how best to support a broad-based economic recovery in Scotland. This advice clearly recognised the uneven impacts of the pandemic across the country and the need for multiple responses: “Different solutions will be needed in different parts of the country... Scotland's recovery planning needs to be place-based, building on local assets and on the role and powers of local authorities and their partners” (p. 28). Critically, it also emphasised the importance of understanding the economy as multidimensional, consisting of human and social capitals (people's skills and experience, and social cohesion, respectively) and natural and environmental assets which act in addition to, and support, business activities (p. 18). Aligning with this framing, the Government’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation, published in 2022, defines the ‘Wellbeing Economy’ as Scotland’s economic vision: “a society that is thriving across economic, social and environmental dimensions, and that delivers prosperity for all Scotland’s people and places” while addressing the country’s long-term social and spatial inequalities. As traditional economic indicators, like the gross domestic product (GDP) are inadequate for measuring this type of development, we urgently need to understand what characteristics can best enable a wellbeing economy, where these are located, and the extent to which different communities and places have access to and use of them. This is particularly the case as while the ‘Higgins report’ was published during the crisis of Covid-19, Scotland’s economy and society are clearly being affected by overlapping crises: not least, significant increases in the cost of living, energy and housing; the continuing effects of Brexit; and extremes of weather and climate. Additionally, complex longer-term challenges in many rural and island communities – not least, population imbalances and poor access to services – impact on their resilience and potential for economic development.

At the James Hutton Institute, we’re involved in three long-term strategic research projects on ‘Rural Futures’, covering the rural economy, rural communities and land reform. The first of these projects takes a holistic approach to the Scottish rural economy to identify paths towards a just, sustainable recovery, and inform rural policymaking. We aim to create new, freely available insights and evidence on rural diversity, including the assets essential for enabling a wellbeing-focused recovery, and place-based outcomes. We want to better understand how people make decisions about key economic issues. We will carry out in-depth research which is co-designed with communities to learn, in ‘real time’, about the changes taking place in these and their impacts on economic development; intending to support communities to achieve their goals. And we intend to develop an advanced model of the rural economy and communities, incorporating insights from all these activities and methods, potentially allowing decision-makers to understand how scenarios and changes could affect different areas.

In February 2023, our research team were delighted to welcome seventeen experts from organisations involved in rural economic development across Scotland to two workshops, which considered the question "What assets are needed by rural and island communities to enable a wellbeing-focused recovery?". Recognising how many types of work contribute to rural development, the organisations invited were diverse and included the environmental, agri-food and land-based sectors; education and skills; private enterprise; community development; culture; housing, energy and transport. For these workshops, assets were defined very broadly as “the resources that characterise a place and the people that live there, which can benefit the local community and businesses in some way”, with the ‘four capitals’ (p. 11) presented as a prompt (but not a guide) for ideas and discussion. In each workshop, the participants were divided into smaller groups and were led into the discussion by a facilitator. Using digital sticky notes, a note-taker compiled all group members’ interventions onto an online whiteboard. Across five breakout groups in the two workshops, we collected a total of 206 sticky notes.

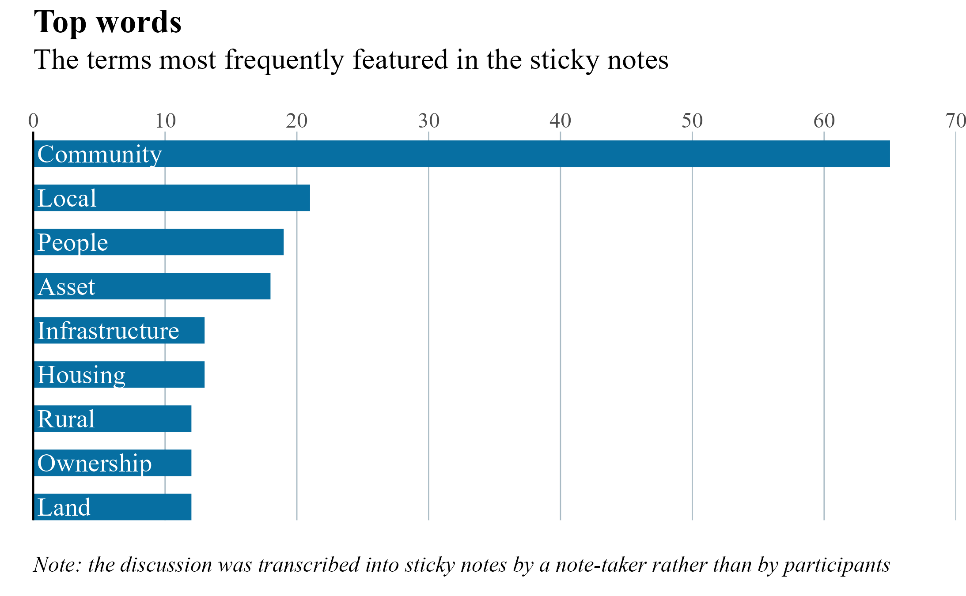

We have explored and analysed the raw text data collected in the workshops. The first step has been to simplify the corpus of sticky notes by turning it into a “bag-of-words” – an unstructured multiset of words – and removing terms that do not add meaning such as articles or prepositions. To visualise the key concepts, we have ranked the terms in our bag-of-words and arranged them by frequency in a bar chart (below) which allowed us to draw out some initial observations. The conversations in the workshops frequently used the term “community”. Another interesting finding is that the terms “local” and “people” were used in sticky notes with similar frequency – discussions brought up both place-based and people-based assets, which seems to suggest a complementarity between the two. Further, physical assets featured prominently in the discussion, with terms such as “infrastructure”, “housing”, and “land”, accompanied by a focus on “ownership”.

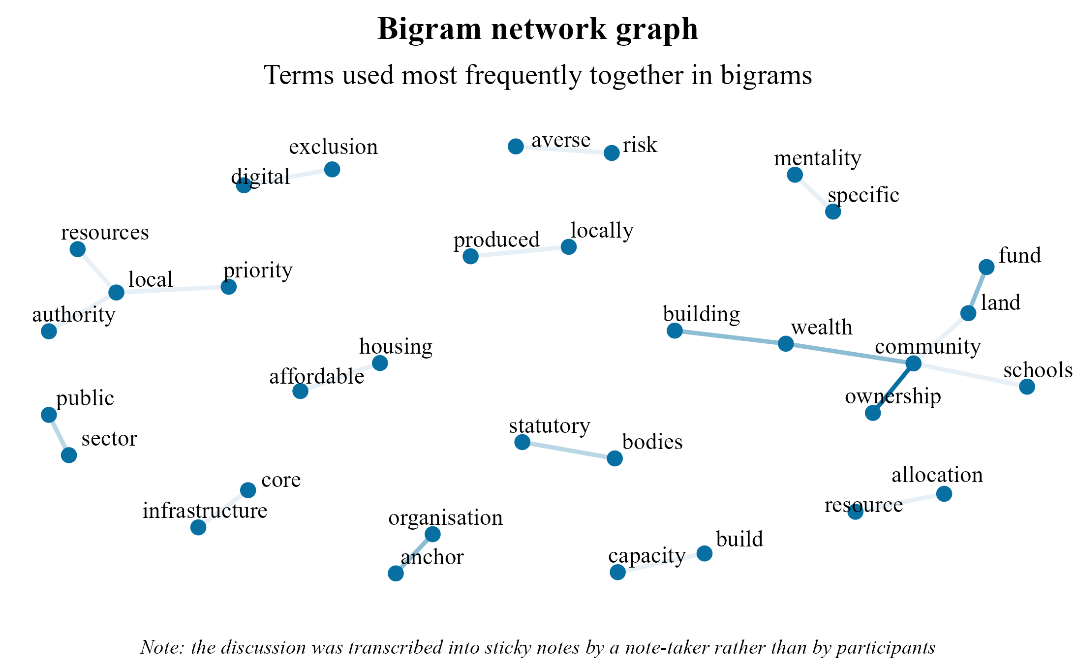

To take the analysis further, we decided to consider the way words were used in relation to each other. Therefore, starting again from the raw text from the sticky notes, we extracted all bigrams – pairs of consecutive words – and plotted the most frequent ones on a network graph (below). The graph shows the top word relationships in our data; words more frequently featured with each other are linked by a darker blue line. Once again, the term “community” features prominently as the one most relationships stem from. Many of the word pairs in the graph relate to physical and tangible assets, things that can be owned and which constitute wealth – confirming the trend identified through our initial analysis. Some of these assets are services and infrastructure outside of business enterprise ("digital exclusion”, “community schools”, “affordable housing”, “core infrastructure”) which contribute to other forms of value and can support business development. But new themes also emerge, through word pairs that relate to local organisations (“public sector”, “anchor organisation”, “produced locally”, “statutory bodies”), or to attitudes and capabilities (“risk averse”, “capacity build”, “specific mentality”). These suggest characteristics which may enable, or present barriers to, the use of assets.

These observations are preliminary, but suggest that a diverse range of physical and social characteristics contribute to developing a wellbeing economy, and that understanding the factors which enable or inhibit the use of these assets is also very important. The next step in the analysis could be to develop a more systematic classification of the themes that emerged in the discussion around assets, possibly by using an unsupervised machine learning model to identify underlying topics in our data. In the short term, we will synthesise the data collected in these workshops to an inventory which will contribute to our data analysis and modelling. Our new datasets and outputs will be published openly, and we hope that these will be useful to as many people as possible.

This work was supported by the Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division (JHI-E1-1).